By Jeff Olson

I seriously doubt that there is anyone reading this article who hasn’t enjoyed the convenience of making a photocopy of a picture or document. Today, we take this technology as a given and for granted. And, most of us probably have never given much thought to how this marvel ever came to be.

Chet was born on February 8, 1906, in Seattle, Washington, the only child of an itinerant barber. Upon resetting in San Bernardino, California, and at age 14, he began working after school and on weekends to support his family. His father was crippled with arthritis, and his mother died of Tuberculosis when he was 17. One of his jobs was working for a local printer, from whom he acquired (in return for his labor) a small printing press about to be discarded. He used the press to publish a little magazine for amateur chemists. Even as a boy, Chet was fascinated with graphics and chemistry. In his words, “work outside of school hours was a necessity at an early age, and with such time as I had, I turned toward interests of my own devising, making things, experimenting, and planning for the future. I had read of Thomas Alva Edison and other successful inventors, and the idea of making an invention appealed to me as one of the few available means to accomplish a change in one’s economic status, while at the same time bringing to focus my interest in technical things and making it possible to make a contribution to society as well.”

After graduating from high school, Chet worked his way through a nearby junior college where he majored in chemistry. He then entered the California Institute of Technology, where he graduated in two years with a degree in physics in 1930. Job opportunities were very limited at the time, though he applied to 82 firms and received only two replies before finally securing a $35-a-week job as a research engineer at Bell Telephone Laboratories in New York City. While working at Bell Labs, Carlson wrote over 400 ideas for new inventions in his personal notebooks. He kept coming back to his love of printing, especially since his job in the patent department gave him new determination to find a better way to copy documents.

As the Great Depression deepened, he was laid off at Bell, worked briefly for a patent attorney, and then was hired by an electronics firm, PR. Mallory & Company. While there, he studied law at night and earned a law degree from New York Law School in 1939. Chet was eventually promoted to manager of Mallory’s patent department. As he later recalled, “I had my job, but I didn’t think I was getting ahead very fast. I was just living from hand to mouth, and I had just gotten married. It was kind of a struggle, so I thought the possibility of making an invention might kill two birds with one stone: It would be a chance to do the world some good and also a chance to do myself some good.”

While at his job, Chet noticed that there never seemed to be enough carbon copies of patent specifications, and also no quick or practical way of getting more. As the old saying goes, “necessity is the mother of invention.” So, Chet had two choices: He could send for expensive photocopies, or he could have the documents retyped and then reread for errors. It then occurred to him that offices might benefit from a device that would accept a document and make copies of it in a matter of seconds. For months Chet spent his evenings at the New York Public Library reading all he could about imaging processes. As he saw it: “The need for a quick, satisfactory copying machine that could be used right in the office seemed very apparent to me—there seemed such a crying need for it—such a desirable thing if it could be obtained. So I set out to think of how one could be made.”

With an inventor’s instinct, he decided to “think outside the box,” as we would say today. He pursued the little-known field of photoconductivity and primarily the work of Hungarian physicist Paul Selenyi who was experimenting with electrostatic images. Chet learned that when light strikes a photoconductive material, the electrical conductivity of that material is increased.

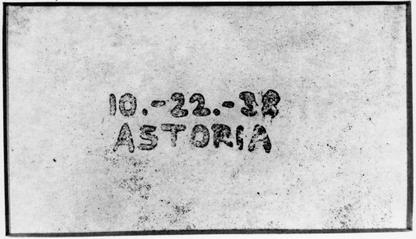

He began some experimenting in his home in Jackson Heights, Queens, to convert his theory into practice. He poured what few resources he had into his research and set up a small lab in Astoria, Oregon in 1934. He hired a young German physicist named Otto Kornei to assist in the lab. It was in this lab, a rented second-floor room above a bar, where they discovered the core fundamentals of what Chet called electrophotography, which was later named xerography. As he stated, “I knew that I had a very big idea by the tail, but could I tame it?” He filed his first preliminary patent application on October 18, 1937. In September 1938, he applied for a patent based on the principles of electron photography. A month later, he and Otto made the first electrophotographic copy. It read simply “10-22-38 Astoria.” The patent application was filed in April 1939, and eighty years ago this week, October 6, 1942, Chet’s patent (U.S. Patent 2,297,691) was issued.

Any concern Chet may have had about other scientists taking the same path or trying to copy (no pun intended) his ideas was unfounded, to say the least. He and he alone was blazing this trail, having no contemporaries who believed there ever would be any practical value to xerography. From 1939 to 1944, he was turned down by more than 20 companies in his search for one that would develop his invention into a useful product. As he stated, “The years went by without a serious nibble…I became discouraged and several times decided to drop the idea completely. But each time I returned to try again. I was thoroughly convinced that the invention was too promising to be dormant.”

At last, in 1944, Battelle Memorial Institute, a non-profit research organization, showed enough interest to sign a royalty-sharing contract with Chet and began to develop the process. Seventy-five years ago, in 1947, Battelle entered into an agreement with a small photo-paper company called Haloid (later to be known as Xerox), giving Haloid the right to develop a xerographic machine.

In 1959, the first office copier using xerography was marketed. The 914 Copier could make copies on plain paper quickly at the touch of a button. It was a huge success and made Chet a wealthy man. Today, xerography is the foundational cornerstone of a huge worldwide copying industry, including Xerox and other corporations which make and market copiers and duplicators.

Chet’s determination and belief in his cause finally paid off, but Chester Floyd Carlson was not in it for the money. He had always lived quite modestly, even after becoming wealthy, and was very generous with his fortune. During his last years, he was given dozens of honors for his pioneering work, including the Inventor of the Year in 1964 and the Horatio Alger Award in 1966. All the fame, wealth, and honor he received was met with the grace and humility of a reserved, quiet and gentle soul – a man who had given away most of his wealth to various foundations and charities by the time of his death in 1968. In 1981 Carlson was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. He once said, “You are successful the moment you start moving toward a worthwhile goal.” By that standard, or about any for that matter, Chet was more than successful!

Chester Carlson was honored as “The Father of Xerography” when United States Public Law 100-548 was signed into law by Ronald Reagan, designating October 22, 1988, as “National Chester F. Carlson Recognition Day.” He was honored by the United States Post Office with the issue of a 21-cent stamp.

Jeff Olson, Author

✽Images courtesy of Xerox Corporation by http://news.xerox.com/pr/xerox/photo.aspx?fid=93941&id=E0C18647, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=28655314

How a man could persevere like he did was quite impressive. Who would have thought!