Reflections from History and Faith

By Jeff Olson

In recent American history, there has been and still is much discussion and debate in regard to “rights.” We’ve seen a plethora of rights emerge and overwhelm America’s legal landscape, and to the point where the entire concept of rights has been turned upside down. While this has yielded some positive results, it has also helped to advance an entitlement mentality that uses the language of rights as an avenue to give moral force to what are often actually privileges or merely personal desires.

The traditional understanding of rights was defined as something to which one has a just claim and something that one may properly claim as due. This included the freedom to act by your conscience without fear of interference from another person or from the government (provided the act was not subversive to order) with the understanding that every right is wedded to some duty, and the exercise of rights is justified only if the claimant of rights stands ready to fulfill the corresponding duties. Our Founders understood the fact that the Creator gave humans a special place among all other creatures, making them free with the capacity for faith and reason, and endowing them with an incomparable dignity within the created order. This undergirds equality among men/women which is not an inherent revelation from man’s capacity for reasoning, but a product of his appeal to a biblical metaphysic and Christian faith which lay claim to transcendent truth – truth which led our nation’s founders to subscribe to two venerable concepts of human equality: equality before the law and equality in the judgment of God. This governmental philosophy is uniquely American. The concept of Man’s natural rights being unalienable is based solely upon the belief in their Divine origin. In other words, certain rights are understood to be pre-political, not given by government but rather to be protected by government. These rights arose out of an appeal to natural law and were understood to be the birthrights of every free American. Those rights were also anchored deep in English common law and in the history of the American colonies. The emphasis on rights in America’s founding documents was intended to limit state power – to define specific areas free from government control. This transformation of rights has actually expanded state power and asked government to regulate many aspects of our lives which were once private – thus essentially re-defining not only rights but also the role of government itself. For each new right that is created, an entire network of laws and regulations is written to enforce the corresponding obligations. It is indeed ironic that as Americans demand more rights, we enjoy fewer freedoms.

The Declaration Of Independence was, among other things, a promissory note to those whose lives it could not immediately bring equality in society. However, its precepts inspired and set into motion America’s long, arduous and costly journey from declaring human equality and rights to securing and protecting them through codified law. It was however a journey that could have occurred and made such progress only in a country with a moral foundation and social/civil order such as ours.

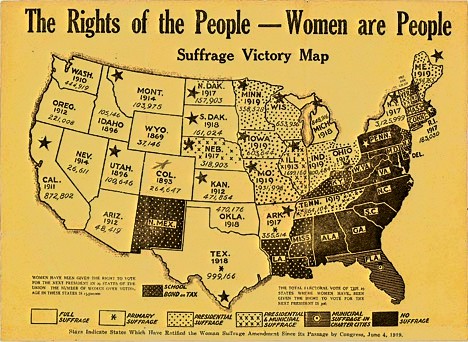

One of the civil rights which needed to be recognized and codified during this journey was that of voting for women. One hundred two years ago, August 18, 1920, the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified, legally confirming for women the right to vote. Here, our republic functioned as it was designed to through the Constitution, responding to the voice of the people (through the states) in applying a principle of equality enshrined in our Declaration of Independence.

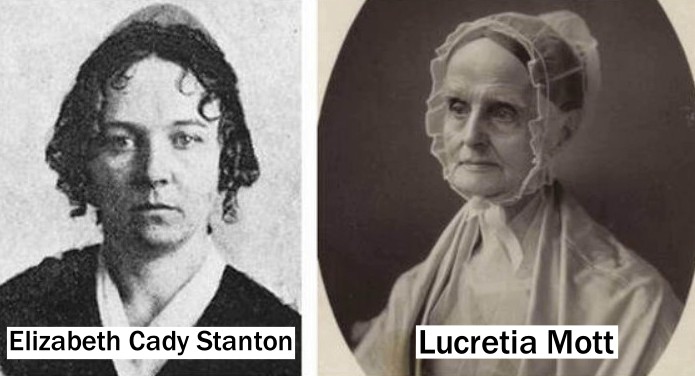

The battle for women’s rights, however, began many years prior to 1920. In 1840, American abolitionists Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott traveled to the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London. There, they discovered that women could not participate; rather they had to sit in a separate area curtained off from the main proceedings. The injustice of women not being allowed to participate in a meeting about freedom was both ironic and tragic to both women and, as a result, each vowed to someday hold a convention to discuss women’s rights. Eight years later, that convention became a reality.

On July 19, 1848, America’s first conference on women’s rights, the Seneca Falls Convention, took place in the Wesleyan Chapel in Seneca Falls, New York. Stanton opened the convention and read a Draft Declaration of Rights and Sentiments, modeled on the Declaration of Independence. It read, “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal.” The conference included a resolution calling for women to have rights and responsibilities equal to men and a resolution for suffrage for women. This convention not only helped to launch a movement that would lead to women’s voting rights in America, but it would open the door to other future opportunities for women and others in America and in much of the world.

I for one am very thankful for the long overdue advancement in granting women the legal right to vote. Almost as much as this though I am grateful for the responsibilities women have been taking and still are taking at various levels of the political process – all the way from working the polls at election time to political party participation and leadership to serving in public office. Not only are their contributions monumental, but often they are indispensable.

Thank you, ladies!