As a child, I was very blessed in many ways. One of those ways was having a good mother who was also a good cook, and a part of that was her pancakes. She often made those from scratch, but when she didn’t, she used a pancake mix, though, of course, it wasn’t nearly as good. The pancake syrup was always store-bought, and we had our favorite of that as well.

Come to find out, that lady was Nancy Green. Born into slavery in 1834 in Mount Sterling, Kentucky, Nancy Hays (or Hughes) married George Green, and together they farmed and had several children. Sometime during her late teen or early twenties, Green obtained her freedom and began work in Covington as a nurse and housekeeper for the Charles Morehead Walker family. Eventually, the family moved to Chicago and took Green with them.

After the Civil War, Green became a strong voice at Olivet Baptist Church, a church she co-founded and the city’s oldest black congregation, a congregation of about 9,000 members. This church was well known for its work to protect those who had escaped slavery because there were many slave catchers in Chicago still pursuing people who were of African descent. She also was a strong advocate against poverty and supported organizations fighting for civil rights. But as we shall soon see, this wasn’t to be the full scope of Nancy’s legacy.

In 1888, newspaper editor Chris Rutt and his business partner Charles Underwood purchased the Pearl Milling Company with the idea of perfecting a recipe for a self-rising, premixed pancake flour. According to M. M. Manring, author of “Slave in a Box”: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima,” Rutt and Underwood had considerable difficulty branding it. In St. Joseph, Missouri, Rutt happened upon a performance of “Old Aunt Jemima,” a popular minstrel song written by Black musician Billy Kersands in 1875. The song features a mammy, a racial stereotype of the Black female caretaker figure devoted to her white family. This image of Southern hospitality inspired Rutt with an idea to use this image to promote his product.

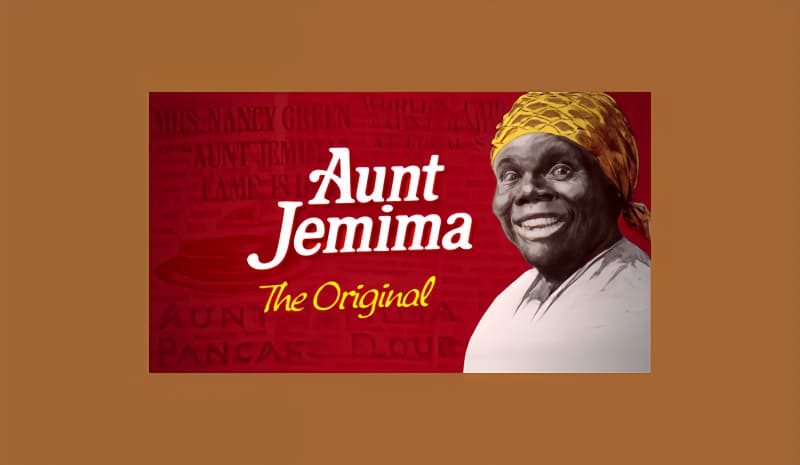

Unfortunately, Rutt and Underwood could not sell their newly named Aunt Jemima breakfast product. With no distribution network and little understanding of the advertising business, the partners eventually sold their company and the recipe to R.T. Davis, owner of R.T. Davis Milling Company, the largest flour mill in St. Joseph, Missouri. Davis, having worked in the flour industry for decades, was able to invest the necessary capital in improving the Aunt Jemima recipe, plus he also knew how to market the product successfully. He decided to promote Aunt Jemima Pancake Mix by creating Aunt Jemima in person. After merging his company with the Pearl Milling Company in 1890, Davis sent a casting call for a gregarious, theatrical Black woman who could cook the pancake mix at big demonstrations. In 1890, Nancy Green, a 59-year-old servant for a Chicago judge, was hired for the role. She became the first and most influential Aunt Jemima.

Dressed as Aunt Jemima, Green appeared at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago beside the “world’s largest flour barrel” (24 feet high), where she operated a pancake-cooking display, sang songs, and told romanticized stories about the Old South. Her exhibition booth drew so many people that special security personnel were assigned to keep the crowds moving. She also appeared at fairs, festivals, flea markets, food shows, and local grocery stores with her arrival heralded by large billboards featuring the caption, “I’se in town, honey.” Green’s engaging personality and talent as a cook for the Walker family, whose children grew up to become Chicago Circuit Judge Charles M. Walker and Dr. Samuel Walker, helped establish a successful promotion of the product. Columbian Exposition officials proclaimed Nancy Green “Pancake Queen,” and she received a medal and certificate from the Expo officials. She was signed to a lifetime contract and traveled on promotional tours all over the United States; however, her role as Aunt Jemima lasted only for about 20 years.

As a result of Nancy’s promotional work, flour sales greatly increased, and the image of pancakes changed immensely. Until she aggressively promoted the Aunt Jemima Self-Rising Pancake Flour Mix, the flour business had been strictly seasonal, with most sales occurring in the winter. People began purchasing and using pancake flour all year around, and pancakes evolved from being strictly a breakfast menu item into standard lunch, dinner, and late supper fare as well. This huge success was a tribute to Nancy Green’s gifts and talents. Her personality was warm and appealing, and her showmanship was exceptional.

Other ladies would model Aunt Jemima beginning in about 1900, including Agnes Moody, Lillian Richard, Tess Gardella, Amanda Randolph, Edith Wilson, and Aylene Lewis. However, it was Nancy Green’s personification of Aunt Jemima and the character’s mythology originally established by R.T. Davis that set the course of propelling the pancake into the kitchens of American homes and provided fame for Green and fortune for the subsequent ownership companies. There is no evidence to indicate Green ever saw any revenue from the Aunt Jemima brand.

In 1910, at age 76, Green was still working as a residential housekeeper, according to the census. Not many people were aware of her role as Aunt Jemima. Green lived with nieces and nephews in Chicago into her old age. She died 100 years ago this week, on August 30, 1923, at age 89, when a car driven by pharmacist Dr. H. S. Seymour collided with a laundry truck and “hurtled” onto the sidewalk where Green was standing. By the time of her death, she had already lost her husband and children and was living with her great-nephew and his wife. She was buried in a pauper’s grave near a wall in the northeast quadrant of Chicago’s Oak Woods Cemetery. Her grave was unmarked and unknown until 2015.

Sherry Williams, founder of the Bronzeville Historical Society, spent 15 years uncovering Green’s resting place. Williams received approval from a distant relative of Green’s (Marcus Hayes, Green’s great-great-great-nephew) to place a headstone. Williams reached out to Quaker Oats about whether they would support a monument for Green’s grave. Their corporate response was that Nancy Green and Aunt Jemima aren’t the same – that Aunt Jemima is a fictitious character. The headstone was placed on September 5, 2020. In William’s words, “Black mothers are not irrelevant. I look at Nancy Green as a Black mother figure and Black women are the lifelines for generations, both Black and White.”

The R.T. Davis Milling Company was renamed the Aunt Jemima Milling Company in 1913. In 1925, the Quaker Oats Company entered into a contract to purchase the Aunt Jemima brand. For almost a century after Nancy Green’s death, some version of Aunt Jemima’s image would remain on the pancake mix box and syrup bottle. When PepsiCo acquired the Quaker Oats Company and the Aunt Jemima brand in 2001, the company said the brand had “the goal of representing loving moms from diverse backgrounds who want the best for their families.” Quaker Oats announced in June 2020 that it would remove Aunt Jemima’s image. Along with this, there was also a change in the brand name. This was decided on the premise that the image was “based on a racial stereotype.” In February 2021, Quaker Oats announced the pancake mix and other products would be renamed “Pearl Milling Company,” an homage to the original mill built in 1888. The new name and logo began appearing on packages in June 2021. However, there remains a small Aunt Jemima reference on the pancake mix box and the syrup bottle, reminding us of Nancy Green’s legacy and of days gone by when her smiling face graced the label and our table.

In the days and years to come, when we sit down to enjoy that stack of pancakes topped with butter and doused in syrup, regardless of the brand, I hope we will remember Nancy Green and her role in the history of the pancake and especially its rise to prominence as an enduring staple of American culture.

By Jeff Olson