Medals of honor of the three military departments

REFLECTIONS FROM HISTORY AND FAITH

BY JEFF OLSON

As I sit down to write this, it is the 4th of July, 2023. I’ve been in deep reflection about our country over the past 24 hours, and especially since waking up early this morning. I’ve read some scripture, listened to some Christian music and patriotic music, and thought some about those of our forefathers who committed their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor to the cause of individual liberty and national freedom.

Their cause was and still is the cause of mankind, and it has been the duty of a free people to maintain our Declaration of Independence as much as it was the duty of our forefathers and foremothers to implement it, and may I say against overwhelming odds. They believed with all their heart that liberty was so much more important than security.

The cost of maintaining that Declaration, our Constitution, and our way of life has been an enormous and indispensable one for those who’ve worn the uniform of the U.S. military. There have been over 1.3 million military deaths since 1775.

Some of these men were boyhood heroes of mine. Their courage, valor and love for America were positive examples for me and helped to shape me into who I am today. However, I’ve never forgotten the courage and sacrifice of all the other men and women in uniform who paid their own price in service to America. My father was one of those.

In the following paragraphs, I wish to briefly share some history of how those who went above and beyond the call of duty have been officially recognized and honored.

The first formal system for rewarding acts of individual gallantry by America’s fighting men was established by General George Washington in August 1782. Designed to recognize “any singularly meritorious action,” and later “For military merit and for wounds received in action,”the Badge of Military Merit took the form of a heart made of a purple cloth.

The idea of a decoration for individual gallantry remained through the early 1800s. In 1847, after the outbreak of the Mexican-American War, a “certificate of merit” was established for any soldier who distinguished himself in action. No medal went with the honor. After this war, the award was discontinued; therefore, no military award remained to recognize the nation’s fighting men.

Some 15 years later, early in the Civil War, a medal for individual valor was proposed to General-in-Chief of the Army Winfield Scott, but he rejected the idea. However, the Navy liked the idea and acted on it. On December 9, 1861, Iowa Senator James Grimes introduced Congressional legislation for the creation of the Medal of Honor in the Navy. It was signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on December 21, 1861. The medal was “to be bestowed upon such petty officers, seamen, landsmen, and Marines as shall most distinguish themselves by their gallantry and other seamanlike qualities during the present war.”

The following year, a resolution similar in wording was introduced on behalf of the Army. On February 17, 1862, Senator Henry Wilson introduced Congressional legislation for the creation of the Medal of Honor in the Army. It was signed into law 161 years ago this week, on July 12, 1862. The measure provided for awarding a medal of honor “to such noncommissioned officers and privates as shall most distinguish themselves by their gallantry in action, and other soldierlike qualities, during the present insurrection.” Although it was created for the Civil War, Congress made the Medal of Honor a permanent decoration 160 years ago, in March 1863.

The Medal of Honor was first presented later that month to Union soldiers of the Andrews’ Raiders who had gone on a spy mission into Georgia, decommissioning a railway and telegraph lines in the process. The first Navy Medal of Honor, presented on May 15, 1863, went to Robert Williams of the U.S.S. Benton. John F. Mackie of the U.S.S. Galena was the first Marine to receive the Medal, presented on July 10, 1863.

In 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt mandated through Executive Order that the Medal of Honor should always be presented with ceremony by the President or a designated representative. In 1916, the Army & Navy Medal of Honor Roll was created and the first special pension for recipients began. In 1916-1917, Congress conducted a review of all Medal of Honor Awards up to that point to ensure that they met the high standards required for the award. As a result, 911 Medals of Honor were rescinded.

One of those involved was the only woman recipient of the Medal of Honor, Dr. Mary Edwards Walker (1832-1919). The Medal was presented to her in November 1865 by President Andrew Johnson for her meritorious service during the Civil War. It was rescinded because she was a civilian who had never been commissioned an officer in military service. Nevertheless, she refused to return the medal and continued to wear it for the remainder of her life. Sixty years later, in 1977, President Jimmy Carter restored the Medal of Honor to Walker’s name.

During World War I, the Armed Forces realized that having more than one medal for valorous action would be beneficial and allow for the recognition of more deserving recipients. In response, Congress codified the Distinguished Service Cross, the Distinguished Service Medal, and the Silver Star in July 1918. However, The Medal of Honor remained at the top of the “pyramid” of valor.

Over the years the Medal of Honor has undergone several redesigns, with the current design being an inverted star suspended around the neck on a light-blue ribbon with thirteen white stars. The Army and Navy have their own designs, a tradition that started in the Civil War. In 1965 the Air Force, which became its own military branch in 1947, introduced their own design for the Medal of Honor. Prior to this, Army Air Corps and Air Force recipients received the Army’s design. Each branch’s design features differences within and surrounding the pendulous star, but each of the three stands for “action above and beyond the call of duty.”

For an act to be considered for the Medal of Honor, it must be in combat and involve the risk of the service member’s life. The act must be so outstanding that it clearly distinguishes gallantry beyond the call of duty and must be the type of deed which, if not done, would not result in any justified criticism.

To ensure each presentation of the Medal of Honor is warranted, every recommendation goes through an exhaustive review process. Incontestable proof is required, including at least two sworn eyewitness statements and documents. An individual must be recommended for the Medal of Honor within three years of their valorous action and the Medal must be presented within five years. If it is not, Congress must pass a law waiving the time limits.

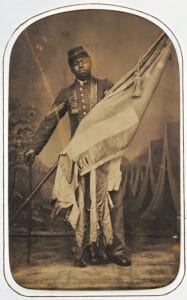

Out of the 41 million who have served in the U.S. military, there have been 3,565 Medals of Honor presented (as of March 30, 2023). Among these, there have been 19 recipients of two Medals of Honor. Of the total, 618 medals have been awarded posthumously, and only 65 living recipients remain to date. Medal of Honor Recipients have included patriots of various races. As an example, Army Sergeant William Carney was the first African American to perform an action for which a Medal of Honor was awarded, but Navy Seaman Robert Blake (the second African American to perform such action) was the first one to receive his Medal (1864). Carney received his medal in 1900, 37 years after he earned it.

Medal of Honor Recipients receive a special monthly pension for life, may fly for free on military aircraft on a space-available basis, qualify for burial at Arlington National Cemetery, and their children may apply to U.S. service academies without a Congressional sponsor. More information about the Medal of Honor can be found on several Internet sites, including the Congressional Medal of Honor Society website at https://www.cmohs.org/medal.

Just prior to preparing a closing for this piece, I just happened upon one of my very favorite motion pictures, “Sergeant York. “The film never fails to inspire me, and this time it inspired me to include quotes from several Medal of Honor Recipients. Corporal Alvin C. York (U.S. Army 1918): “In the war the hand of God was with us. It is impossible for anyone to go through with what we did and come out without the hand of God. We didn’t want money; we didn’t want land; we didn’t want to lose our boys over there. But we had to go into it to give our boys and young ladies a chance for peace in the days to come.” Petty OfficerMichael E. Thornton (U.S. Navy 1973): “[The] Medal of Honor belongs to every man and woman who gives us the freedom today to be able to hold our flag and hold our heads up high and say we have the greatest country in the world. And that goes with the men and women in the past, and the men and women of today, and the men and women of the future. As long as Mike Thornton lives, that medal will always stand for all them. Not for me. Not for what I’ve done, but for what I was trained to do and what they have been trained to do to give us our freedom today.” Second Lieutenant Daniel Inouye (U.S. Army 2000 – for service in WW II): “I’ve always felt that if I am deserving of the Medal of Honor, there are many, many others who are. I felt a little bad receiving it, so I received it on behalf of the fellows, because there’s no such thing as a single-handed war. There’s always a support group, and if you didn’t have people who supported you, you couldn’t fight a war.”

Source of images: Wikimedia Commons